Quality of swimming waters

INTRODUCTION

The sea is an essential element of our life, source of food and of leisures; it represents, in most Mediterranean countries, a significant part in the economy, thanks to tourism, it concentrates in fact over 30% of international tourism (UNEP/MAP, 2012); its quality has therefore a major importance. These last years, strong urbanization, tourism and democratization of aquatic activities involved an increase in frequentation of the Mediterranean coastline and therefore a degradation of the quality of coastal waters. In this study, we will try to determine the microbiological and physico-chemical quality of the swimming waters of the Gulf of Skikda through the water analysis of a ten station thus covering the entire Gulf.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

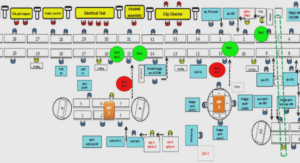

The wilaya of Skikda is located in north-eastern Algeria bordering the Mediterranean Sea and has a coastline of over 140 km long. Our study area gathers two villages and extends over twenty kilometers, it includes, east beaches Filfila and Ben M’hidi about 15 Km and to the west, a road about 3 Km beaches (Fig. 1). In addition the Gulf of Skikda is a discharge point for many wadis: Wadi Safsaf the main one, flowing in the center of the Gulf, and two secondary wadis at Filfila. The samples, transport and analysis of seawater samples were conducted according to guidelines for the monitoring of the quality of swimming waters. This monitoring program was carried out for a period of five months (December 2013–April 2013). The collected data were measured in each seawater sample taken per month per site. The analysis focuses on the quantification of faecal indicator bacteria (total coliforms, faecal and faecal streptococci) using the method of the enumeration in liquid medium by determining the most probable number (MPN); as well as determining certain physicochemical parameters (electrical conductivity, pH, dissolved oxygen, …). The health status of swimming water is assessed based on the results obtained and compared to thresholds, quality bacteriological and physicochemical criteria present in the Executive Decree No. 93-164.Moreover, in order to compare the averages of the different physico-chemical parameters measured between the ten sites, we used the test of the analysis of variance in a criterion of classification (ANOVA), fixed pattern.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Regarding the average results recorded for the various physico-chemical parameters, we note that those are in adequacy with the quality standards required for swimming waters by the standards in force (Table 1). The temporal variation of the concentrations of different germs sought shows that they fluctuate in the same way showing their dominance during the month of December (Fig. 2). This can be justified by climatic conditions recorded during this month which resulted in the discharge of rainwater directly into the sea without treatments, the high flows of urban waste and wadis, the agitation of the water, etc. (Mazières, 1963). Moreover, presence of enteric bacteria in the sea water can be justified by several phenomena and is conditioned by a number of specific parameters including: – Physical factors: temperature, absorption / adsorption, dispersion, dilution, sedimentation, light (bactericidal radiation at shallow depths only) (see Carlucci & Pramer, 1959; Brisou, 1968; UNEP / WHO, 1983; Pommepuy et al., 1991; Gourmelon, 1995); – Chemical factors: salinity (selection factor), and dietary deficiencies in vitamins, fasting, dissolved oxygen (Carlucci & Pramer, 1959; Brisou, 1968); – Biological factors: microphage plankton or adsorbent, benthos and nekton (macrophage-plankton), vital competition, bacteriophages (Brisou, 1968; Oger et al., 1983; Gourmelon., 1995). All these factors act together; either simultaneously or in successive steps in time and in space, to reduce the number of bacteria or eliminate them. The spatial variation of the concentrations of different germs sought allows us to see that as, a whole, the average results recorded are in adequacy with the quality standards for swimming waters except for the fourth site where registered rates are significantly higher than the limit values required for fecal coliforms and fecal streptococci (Fig. 3). The results obtained at the fourth site, namely the “Beach la jetée » shows a fecal contamination and, Figure 1. Location of the study area and sampling sites, Gulf of Skikda, Algeria. therefore, its poor bacteriological quality. The presence of an urban emissary explains these results and justifies its permanent closure for swimming. Moreover, analysis of total coliforms does not allow to assess the quality of water because a great heterogeneity of species is grouped under this term. In fact, some of them are certainly of fecal origin and may reflect a fecal pollution of water, but others are found naturally in the soil or vegetation (Rodier et al., 2005); Today, only the detection of fecal coliforms, specifically Escherichia coli and intestinal enterococci, in water must seriously let suspect fecal contamination, since they are the most reliable enteric pathogens, and therefore the best way to detect recent fecal contaminations (Payment & Hartmann, 1998; Scientific Group on Water, 2003). The results of the univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the five physicochemical variables measured, allow us to note the lack of significant differences between the waters of the ten sites studied (Table 2), which confirms our previous observations as to the equivalence of swimming waters sites studied from the physico-chemical point of view.