ETS: Effector-Triggered

Susceptibility Despite the fact that PTI inhibits infection, successful pathogens have developed strategies to defeat PTI by secreting virulence factors known as effectors to lead effector-triggered susceptibility (Kawamura et al.; Kawamura et al. 2009b) and pathogen virulence (Fig. 1.2B). Extensive work on function of effectors has been done on bacterial effectors where several were found to suppress or disrupt PTI, ETI, or both (Guo et al. 2009), but remarkable advances have also been made in Cladosporium fulvum and oomycetes. In C. fulvum, the A VR2 effector inhibits at least four tomato cysteine proteases that are believed to be crucial in the basal ho st defense (Rooney et al. 2005), while a chitin-binding protein A VR4 protects fungi from the Iytic activity of plant chitinases (Van den Burg et al. 2006). Another effector from C. fulvum, ECP6, is believed to be involved in the chitin fragments scavenging activity that are secreted during infection from fungal cell walls, hence preventing them from functioning as P AMP triggering molecules (Bolton et al. 2008).

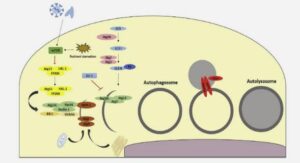

In oomycete species of the genus Phytophthora, elicitins such as INFI triggers a range of defense responses, including programmed cell death in diverse plant species, and are thus considered as P AMPs (Kawamura et al. 2009a). Recently, the P. infestans A VR3a effector has been shown to interact with and stabilize ho st U-box E3 ligase CMPG l, which is required for the triggering of INF I-dependent cell death (Bos et al. 2010). Another oomycete effector from Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, ATR13, has been shown to suppress callose deposition, a presumed basal defense response (Sohn et al. 2007). There is ample evidence now that one function of effectors is to suppress PTI through interaction with pattern recognition receptors (PRR) and processes downstrearn of PRR and rnitogenactivated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Block et al. 2008). Upon pathogen attack, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) activate patternrecognition receptors (PRRs) in the host, resulting in a downstream signaling cascade that leads to PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI). B) Virulent pathogens have acquired effectors (purple stars) that suppress PTI, resulting in effector-triggered suseeptibility (Kawamura et al. 2009). C) ln tum, plants have acquired resistanee (R) proteins that recognize these attacker specifie effectors, resulting in a seeondary immune response called effeetor-triggered immunity (Kunjeti et al. 2016).

ETI: Effector-triggered immunity Luckily, the plant has an additional defense layer through which these effectors can be directly or indirectly be recognized by the plant defense system. This second layer is called Effector triggered immunity, and involves mostly intracellular receptors that are the products of the c\assically defined resistance R proteins (Fig. 1.2C) (FIor 1971). These receptors recognize the presence of effectors of the pathogen by direct binding or indirectly by detecting their activity in the ho st cells, leading to a faster and stronger version defense response th an PT! (Bolier and He 2009). ET! is extremely specific to a race or strain of pathogen as it recognizes a virulence determinant or its effect (Mur et al. 2008). The outcome of ET! is usually the programmed cell death response called the hypersensitive response (HR) at the site of pathogen infection, which is thought to limit the spread of the pathogen from the infection site (FIor 1971).

Natural selection drives pathogens to suppress ET! again, either through diversifying their effector repertoire or by acquiring new effectors. Nevertheless, natural selection also drives plants to modify their R proteins arsenal or acquire new ones, so that the pathogen effectors can be recognized and, again, the ET! can be triggered (hence the zig-zag model). Several proteins secreted in apoplast or xylem sap during colonization of tomato have been identified in C. fulvum or F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici, respectively (Huitema et al. 2004; Thomma et al. 2005), most of which are also avirulence genes that match corresponding resistance genes (Rep et al. 2004; Stergiopoulos and de Wit 2009). In the flax rust fungus Melampsora fini, ail the identified A vr small secreted proteins are expressed in haustoria (Catanzariti et al. 2006; Dodds and Rathjen 2010), however to this date their virulence target are unknown. Similarly, avirulence genes originally isolated from oomycete pathogens encode small secreted proteins, of which transient expression in the ho st cytoplasm leads to R-gene-dependent cell death (Allen et al. 2004; Armstrong et al. 2005; Rehmany et al. 2005; Shan et al. 2008).

Effectors: concepts and definitions

Pathogens have developed strategies to avoid the different levels of host physical and chemical barriers to modify ho st structures and physiology, transforming plant tissues into a suitable niche to obtain the necessary nutrients for their development and ensure the completion of their lifecycle (Gaulin 2017). One of the well-known strategies of pathogens is to secrete an arsenal of molecules called « Effectors » who se various functions aim to promote the success of the infection (Hogenhout et al. 2009; Win et al. 2012). Though the term « effector » is broadly used in the studies of plant-microbe interaction, its definition varies. Kamoun (2003) and Huitema et al. (2004) defined effectors as « molecules that alter the structure and function of ho st cells, thereby facilitating infection (virulence factors or toxins) and triggering defense response (avirulence factors or elicitors). » In another definition Birch and colleagues (2014) referred to effectors in plant-pathogen interactions as « any protein synthesized by a pathogen that is exported to a potential host, which has the effect of making the host environment beneficial to the pathogen ». The widely accepted hallmarks of effectors include; small secreted proteins (SSPs) having a N-terminal signal peptide with low sequence homology across species, no conserved host-targeting signal and capable of manipulating and reprograming host metabolism and immunity (Hogenhout et al. 2009). Most of the described effectors are proteins; however, non-protein effectors have also been described such as metabolites, toxins (Amselem et al. 2011; Arias et al. 2012; Collemare and Lebrun 2011) or small interfering RNAs (Weiberg et al. 2013).

Host-protein targets of effectors

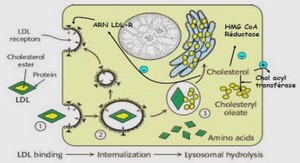

It is now weIl established that the pathogen effectors directly target host proteins and manipulate host targets for their benefit (Rovenich et al. 2014; Win et al. 2012). The first host-targets of plant-pathogen effector proteins to be identified were of bacterial type III effector (T3Es), many of which target positive regulators of immunity in order to inhibit their activity (Des landes and Rivas 2012). One particularly notable example of a ho st target is the A. tha/iana RPMI-interacting prote in RIN4 (Win et al. 2012). Sorne bacterial effectors are enzymes, such as sorne of T3SS delivered effectors which biochemically alter host molecules, such as HopZla which has been reported to physically interact with GmHIDl (2-hydroxyisoflavone). The interaction ofHopZla and GmHID 1 leads to degradation of GmHID 1 and thereby leads to enhanced bacterial multiplication (Cunnac et al. 2009; Deslandes and Rivas 2012). Few effectors do not con vey enzymatic activity; however, they bind to host proteins to alter host cellular functions. In addition to this, many such effectors prevent plant enzymes activity (kinases, glucanases, peroxidases, and proteases) (Song et al. 2009; Tian et al. 2004; Tian et al. 2007). Other groups of bacterial effectors bind nucleic acids and regulate gene expression, for example, Xanthomonas Transcription Activator-Like (TAL) effectors directly bind to promoter motifs of ho st genes to modify host transcription (Boch et al. 2009; Gu et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2006).

SWEET sugar transporters are one of the host susceptibility genes which are induced by TAL effectors (Li et al. 2013). Identification of the effector targets in the host cell remains challenging because of a large number of uncharacterized or unidentified effectors from the diverse group of pathogens, microbes and symbionts. For the same reason, the biochemical mechanisms of how effectors manipulate their ho st target are also poorly understood. Regardless of the specific target of effectors, now it has been reported that a single effector can target multiple plant proteins or can disturb diverse cellular processes in the host (Fig. 1.4) (Win et al. 2012). For example, the P. syringae type-III effectors AvrPto and AvrPtoB in tomato and A rabidopsis, directly bind to several immune receptor kinases to abrogate their function and impede PTI signaling pathways (Abramovitch et al. 2006; GimenezIbanez et al. 2009; Shan et al. 2008; Xiang et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2012). The HopMl effector, degrades several plant proteins, including AtMin7 (Nomura et al. 2006). Similarly, secreted A Y-WB Protein Il (SAP Il), a phytoplasma effector, binds to both class 1 and II of Teosinte branched lICycloidea/Proliferating (TCP) transcription factors (TF), but subverts the class II type TCP TF (Sugio et al. 2011); hence one of the main function of effectors is the suppression of immunity.

Host-protein helpers of effectors

Regardless of the proteins used as effectors target, some plant proteins act as a co-factor for effector function or post-translationally modify effectors in the cytoplasm and are required for the maturation or trafficking of effector prote in to their final subcellular destination within the ho st cell (Win et al. 2012). Therefore, ho st proteins that facilitate effectors maturation or activity, are known as effectors helper proteins (Fig. 1.5A-B) (Win et al. 2012). Several host effector helpers have been identified. Classic examples of helper protein are the cyclophilin (a chaperone) CYP 1. A vrRpt2, a cysteine protease is secreted as an inactive form by P. syringae, but as soon as it is inside the host cell, it interacts with cyclophilin. The association of A vrRpt2-cyclophilin accelerates folding of the effector and cyclophilin activates self-processing of AvrRpt2, aggravating the breakdown of RPMI Interacting Protein 4 (RIN4), the target prote in of AvrRpt2 (Coaker et al. 2005). Another P. syringe type-III effector, HopZla, is activated by cellular phytic acid from the host to become a functional acetyltransferase that acetylates tubulin, a plant target of HopZla (Lee et al. 2012).

Other type-III effectors require host-mediated biochemical modifications, like myristoylation and phosphorylation, to become functional. Myristoyl transferase is an example which myristoylates the A vrPto T3SS secreted effector of Pseudomonas syringae. Myristoylation of A vrPto and A vrRpm 1 is necessary for their avirulence and virulence activities, suggesting that plant N-myristoyl transferase act as a host-cell helper to the effector (Anderson et al. 2006; Nimchuk et al. 2000). The plant protein importin-a is an another well-studied helper protein that mediates nuclear trafficking and is exploited by several pathogen effectors, including SAP 11, T AL and Crinklers (Bai et al. 2009; Schomack et al. 2010; Szurek et al. 2001). T AL effector A vrBs3 interacts with importin which enables its accumulation in the host-ce Il nucleus where it directly binds to plant DNA harboring a conserved promoter element, which is its « real » target, to activate plant gene expression (Kay et al. 2007; Szurek et al. 2001). Therefore, host proteins can act either as an effector helper or target that are taken or manipulated by the pathogen to enable their effector proteins to function and ultimately, establish a state of effectortriggered host susceptibility. Therefore, conceptually the host proteins used as target or helper for the effectors are ho st susceptibility factors (Win et al. 2012).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS |