Miocene benthic foraminifera from Nosy Makamby and Amparafaka

Introduction In Madagascar, fossil foraminifera remain relatively poorly known, with nearly all published studies describing Paleozoic and Mesozoic forms (e.g., Besairie and Collignon, 1971; Ujiie and Randrianasolo, 1977). This gap in knowledge reflects the fact that Madagascar’s fossil record is nearly entirely constrained to either the Jurassic/Late Cretaceous (Krause et al., 2006) or the recent Late Pleistocene/Holocene (extending back a mere 80,000 years; Samonds, 2007). This critical gap spanning most of the Cenozoic has remained largely unknown; this time interval is particularly significant because this is when the ancestors of the modern Malagasy forms are thought to have arrived (Samonds et al., 2012, 2013). Nearshore marine carbonate deposits from Madagascar’s Cenozoic are mapped, but few have been systematically explored. Previous studies include a few published reports from the Eocene and Miocene, listing both invertebrate (foraminifera, bivalves, gastropods, echinoids) and vertebrate fossils. Vertebrates include bony fish, sharks, rays, turtles, crocodylians, and mammals, including a primitive dugongid skull and ribs belonging to the Malagasy seacow Eotheroides lambondrano (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Samonds et al., 2009; Andrianavalona, 2011). Historically, Miocene rocks were first described from western and northwestern Madagascar (Perrier de la Bathie, 1921; Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Hourq, 1949; Besairie, 1956; Besairie and Collignon, 1971). Perrier de la Bathie produced the first detailed work describing the age of these post-Cretaceous formations, and published a geologic section of Nosy Makamby and Cap Tanjona, two of the best known Cenozoic localities (Perrier de la Bathie, 1921). The largest and most comprehensive work to date is that of Collignon and Cottreau (1927); their work is the foundation for our current understanding of the paleontological and geological history of Nosy Makamby. Further west, Baron and Mouneyres (1904) were the first to publish a comprehensive geological description for Amparafaka. However, this region remains poorly described. Some authors have noted the ‘‘occurrence o Miocene deposits’’, without any specific locality information (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Besairie and Collignon, 1971). A preliminary list of foraminiferan fossils and their associated information was first described by Lemoine and Douvillé (1904); this study and subsequent work has focused largely on the genus Lepidocyclina (a large benthic foraminiferan within the Family Orbitoïdidae; Lemoine and Douvillé, 1904; Douvillé, 1908; Beretti, 1973). Collignon and Cottreau (1927) mention the occurrence of only one species (Miogypsina irregularis), and Lavocat published a simple description of the foraminiferans (Lavocat et al., 1960). Despite a few other species listed by Besairie and Collignon (1971), the microfauna of Madagascar’s Miocene remains incomplete and poorly understood. Here, we report the first detailed study of Miocene microfossils from Madagascar, some of which are reported from the island for the first time. In contrast to the relative paucity of Malagasy Cenozoic vertebrate fossils, foraminiferans are frequently wellpreserved and recovered in high abundance, representing an untapped source of valuable paleoecological information. This information has great potential to elucidate this virtually unknown time period in Madagascar’s past history

Geological setting

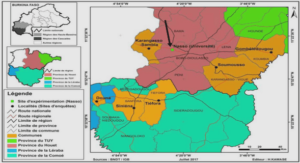

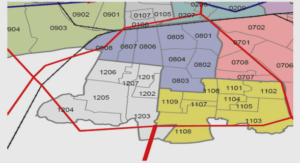

The study region is located within the Mahajanga Basin, northwestern Madagascar (Fig. 1). This region contains the most complete marine sedimentary section of Miocene rocks from Madagascar, with lateral extensions that outcrop in the regions of Nosy Makamby, Cap Tanjona, Cap Sada, and Amparafaka (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Samonds, personal observations). We report here microfossils from two localities: the island of Nosy Makamby, and the coastal region of Amparafaka (Fig. 1). 2.1. Nosy Makamby Nosy Makamby (or Mahakamby1 ) is a small island (about 1.6 km 0.4 km) SSW–NNE aligned offshore at the broad part of the delta at the mouth of the Mahavavy River, in the north-western part of Madagascar, approximately 50 km west along the coast from the regional capital of Mahajanga (Andrianavalona, 2011; Figs. 1 and 2). The island’s sediments are mostly medium to fine-grained calcareous sandstones that accumulated in a coastal near-shore marine environment, overlain by a Pliocene continental unit comprise of red beds and quartz grains, etc. (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Besairie, 1972; Fig. 3); these units are approximately 15 m thick. One horizon is particularly rich in fossilized Kuphus tubes, which clearly demarcates the sediment horizons between exposures on the northern region of the island (Fig. 2). In addition to foraminiferans, a diverse assemblage of both invertebrates and vertebrates have been collected from Nosy Makamby, including bivalves, gastropods, echinoids, crabs, bony fish, sharks, non-diagnostic reptiles (turtles and crocodylians), and sirenian mammals (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927; Besairie, 1972; Samonds et al., 2007).

Amparafaka Within the Baly

Bay, Amparafaka is the most southern of the sites (Fig. 1); no fossils have previously been reported from this region. Like Makamby, Amparafaka is characterized by steep calcareous cliffs covered by red continental Pliocene sandstones. These deposits are interpreted as lateral extensions of those reported at Makamby (Collignon and Cottreau, 1927)