Influence de la méthylation des éléments transposables sur les gènes situés à proximité

Comme décrit dans l’introduction, il semble qu’une perte importante de la méthylation de l’ADN au niveau des séquences répétées, telle celle induite par une mutation dans le gène ddm1, n’ait que peu de conséquences sur la régulation des gènes (Lippman et al. 2004, Vongs et al. 1993). Cette observation est renforcée par le fait que le mutant ddm1 ne présente pas d’altérations phénotypiques majeures (du moins dans les premières générations d’autofécondation). Cependant, ces informations sont quelque peu contradictoires avec les résultats d’une étude montrant que les ET méthylés semblent avoir un effet négatif sur l’expression des gènes à proximité desquels ils sont localisés (Hollister et al. 2011). Afin d’analyser plus avant les conséquences de la perte de la méthylation de l’ADN au niveau des séquences répétées, j’ai participé aux travaux initiés par le précédent étudiant en thèse, Felipe Teixeira, présentés dans le manuscrit en préparation ci‐après. Ma contribution principale concerne les expériences d’ARN‐chip utilisant les puces à ADN CATMA réalisées afin de comparer les transcriptomes des différents mutants. J’ai également généré le triple mutant ddm1rdr2T‐sdc et ai participé à la validation des gènes candidats potentiellement contrôlés directement par la méthylation des séquences répétées situées à proximité.

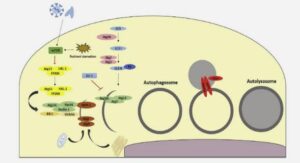

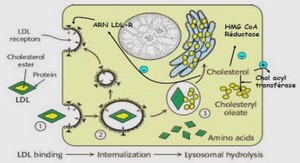

The genetic dissection of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis has uncovered a complex interplay between DNA methyltransferases (MTases), DNA demethylases, histone‐modifying or remodeling enzymes, RNA interference (RNAi) components, and RNA polymerases [1]. Among the actors identified so far, the chromatin remodeler DECREASE IN DNA METHYLATION1 (DDM1; [2]) stands alone as a master regulator of DNA methylation maintenance over repeat sequences [3]. Indeed, mutations in DDM1 lead to a loss of DNA methylation over most repeat elements present in the genome but not over genes. Furthermore, ddm1 mutants exhibit a massive accumulation of transcripts corresponding to repeat sequences, but do not substantially alter the expression of neighboring genes, with few exceptions [2, 4]. Consistent with these observations, early generation ddm1 mutants exhibit only mild phenotypic alterations. However, severe but sporadic phenotypic alterations are observed in advanced generations and result from the mobilization of transposable elements (TEs) into or near genes as well as rare late onset epigenetic alteration of gene expression [5‐10]. In contrast, the RNA‐dependent DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, which targets a majority of methylated repeat elements but not genes [11‐ 14] contributes little to the overall DNA methylation level or the silencing of its targets [12, 14‐17].

We have previously shown that RdDM endows its targets with the ability to regain wild type (wt) DNA methylation following ddm1‐induced loss of DNA methylation [14]. Moreover, we demonstrated that the RdDM pathway is active in ddm1 plants, being able to promote low‐ level DNA methylation over its targets. These observations indicate that DDM1‐dependent DNA methylation and RdDM act concomitantly over a subset of repeat elements. Here, we show that the simultaneous disruption of these two DNA methylation pathways leads to severe, fully penetrant phenotypic alterations as well as widespread changes in gene expression. However, detailed analysis indicates that most of these defects are caused by the misexpression of a few pleiotropic genes and that most genes are insensitive to the epigenetic status of neighboring repeat elements. Taken together, our findings reveal a limited yet critical direct function of RdDM and DDM1‐dependent DNA methylation in preserving normal expression of genes in Arabidopsis.

Compromising together DDM1‐dependent methylation and RdDM leads to severe and fully penetrant phenotypic alterations

To understand better the genetic interplay between RdDM and DDM1‐dependent DNA methylation and their impact on the expression of genes located near repeat elements, we generated mutant plants affected in these two pathways. Double mutant plants were obtained at the expected Mendelian ratio of 1/16 in the F2 progeny of a cross between ddm1 and a mutant line for the RNA DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 2 gene, which is a key component of RdDM (supplementary Table S1). In contrast to these two parental lines however, first generation ddm1rdr2 double mutant plants exhibited severe and fully or nearly fully penetrant phenotypic alterations. These alterations were characterized in the following generation (F3) and included wrinkled leaves, thin stems, small stature, late‐ flowering, and partial sterility (Fig 1). Further selfing led to even more severe defects as well as to the stochastic appearance of additional phenotypes. Similar phenotypic alterations including progressive degeneracy were also observed when the ddm1 mutation was combined with a mutation in the genes NUCLEAR RNA POLYMERASE D2 (NRPD2) or DICER‐ LIKE 2 (DCL2) and DCL3, which encode other key components of RdDM.(supplementary Fig S1). Thus, compromising simultaneously DDM1‐dependent DNA methylation and RdDM causes a robust suite of phenotypic defects. We therefore conclude that these two pathways act redundantly to enable normal plant development.