Dynamiques de l’agrobiodiversité dans les paysages agroforestiers

Les réseaux relationnels pour étudier les modes d’accès des paysan.ne.s aux propagules et aux connaissances

La Partie III se compose du chapitre 7 qui porte sur l’accès des paysan.ne.s de Vohibary aux propagules et aux connaissances relatives à trois espèces agroforestières (bananier, giroflier, vanillier). Ce chapitre vise à mieux comprendre comment les caractéristiques socio-culturelles régissent cet accès et la circulation de ressources et d’informations clés pour la gestion de l’agrobiodiversité. En portant une plus grande attention à leur origine géographique, ce travail discute du rôle des connaissances et des propagules exogènes dans les dynamiques agroforestières et à la résilience des systèmes agricoles . L’approche du consensus culturel repose sur l’idée qu’une connaissance partagée par le plus grand nombre d’individus au sein d’un groupe (par exemple communauté) est une connaissance culturellement partagée et qui fait référence au sein du groupe (Boster 1985, Romney et al. 1986) |Cadre de recherche 69 locaux. Tout ce travail repose sur le cadre théorique et sur le formalisme des réseaux relationnels multi-acteurs (Labeyrie et al. 2019). L’étude des réseaux relationnels s’inscrit dans une perspective (i) de représentation de la diversité et de la complexité des interactions entre des sociétés (systèmes sociaux) et leur environnement (système écologique), (i) d’analyse des processus régissant ces interactions et donc (iii) de compréhension du fonctionnement des systèmes socio-écologiques (c’est-à-dire couplage des interactions sociales et écologiques, Bodin et Tengö 2012). Cette approche est reconnue pour mettre en évidence des modes de gestion durables des ressources naturelles (Bodin et al. 2006, Bodin et Crona 2009), pour appréhender la résilience des systèmes socio-écologiques (Janssen et al. 2006), en particulier de sociétés rurales (Rockenbauch et Sakdapolrak 2017), et plus précisément pour étudier la gestion de l’agrobiodiversité (Labeyrie et al. 2021a). Étudier les réseaux relationnels implique d’employer un formalisme particulier et des méthodes d’analyses relevant de la théorie des graphes (Janssen et al. 2006, Lusher et al. 2013, Labeyrie et al. 2019). Un réseau se compose d’entités sociales et/ou écologiques (nœuds) connectées par des liens résultant d’une interaction entre ces entités (Figure 2-9). Lorsque cette connexion résulte de l’échange d’un objet, il y a circulation de cet objet entre les deux entités : le lien qui les connecte peut être dirigé selon le sens dans lequel se fait l’échange ou il peut être pondéré selon le nombre d’échanges ou la quantité d’objets échangés. Les entités et les liens peuvent être décrits par diverses caractéristiques (attributs). L’analyse d’un réseau (SNA : Social Network Analysis) vise à décrire sa structure (Figure 2-9), en mettant notamment en évidence des motifs structuraux, et à analyser les processus socio-culturels à l’origine de cette structure en mettant en relation ses propriétés structurales (par exemple les motifs structuraux) avec les attributs des nœuds et des liens (processus exogènes) ou avec la position des nœuds dans le réseau (processus endogènes) (Lusher et al. 2013). Dans le cadre de cette recherche, j’ai étudié les réseaux d’acquisition de propagules et de connaissances des paysan.ne.s de Vohibary. La circulation concerne donc deux objets de nature différente : biologique pour les propagules et immatérielle pour les connaissances. Ces réseaux représentent les paysan.ne.s enquêté.e.s et leurs sources de propagules ou de connaissances qui peuvent être de différentes natures, par exemple selon la nature de l’entité ou du lien sociale. Comme je me suis intéressée à trois espèces différentes, les liens peuvent être pondérés si les paysan.ne.s obtiennent plusieurs fois des connaissances et/ou des propagules auprès de la même source. Pour analyser ces processus endogènes et exogènes, la SNA permet de calculer des métriques à l’échelle des nœuds et/ou du réseau global. Cette recherche présente un travail qui s’est focalisé sur l’échelle des paysan.ne.s et qui a analysé leur connectivité (processus endogène) en relation avec leurs attributs. Cette analyse visait à identifier la présence de paysan.ne.s ayant une place centrale dans la circulation car iels donnent des propagules et/ou transmettent des connaissances plus que les autres dans le village. La mise en relation de cette position dans le réseau avec les attributs des paysan.ne.s permet de mieux comprendre quels sont les processus socio-culturels qui influencent les modes |Cadre de recherche 70 d’acquisition et de circulation, et de discuter dans quelles mesures ils contribuent aux dynamiques agroforestières. Figure 2-9: Exemples de différentes structures de réseaux relationnels de paysan.ne.s à l’échelle de leur communauté, avec les nœuds ronds correspondant à des paysan.ne.s et les nœuds carrés à des organisations extérieures à la communauté (figure reprise de Labeyrie et al. 2021a). (A) Réseau centralisé : peu de paysan.ne.s (nœuds oranges) ont un nombre élevé de connexions avec d’autres paysan.ne.s de leur communauté et la majorité estpeu connectes (nœuds bleus). (B) Réseau modulaire : des sous-réseaux (orange, bleu, vert) sont formés par des paysan.ne.s très connectés entre eux en lien avec le partage d’un attribut (par exemple le lieu de résidence, l’appartenance ethnique). (C) Réseau centralisé connecté avec des organisations (par exemple institutionnelle, associative) : le réseau global est très centralisé car peu d’organisations sont connectées avec des paysan.ne.s et inversement. (D) Réseau polycentrique connecté avec des organisations : plusieurs organisations sont connectées avec des paysan.ne.s de sous-réseaux différents qui jouent le rôle de ‘‘passeur’’ entre les organisations et la communauté. |Cadre de recherche 71 Transition : La partie qui suit présente les deux études de caractérisation des dynamiques agroforestières dans le paysage de Vohibary et dans ceux de la zone de Vavatenina. Selon l’échelle considérée, le travail ne visait pas à répondre aux mêmes questions. ▪ À l’échelle de Vohibary : o Quels sont les changements d’occupation du sol qui ont eu lieu entre 1966 et 2016 ? Et quelle place l’agroforesterie occupe-t-elle dans ces changements ? o Quels sont les facteurs socio-économiques et politiques qui ont contribué à ces évolutions et à l’émergence et au développement de l’agroforesterie ? ▪ À l’échelle de la zone de Vavatenina : o Quelle place l’agroforesterie occupe-t-elle dans les paysages par rapport aux autres modes d’occupation des terres ? Son développement est-il homogène sur l’ensemble de la zone ? o Comment la topographie influence-t-elle l’intégration de l’agroforesterie dans les paysages et sa répartition spatiale ? o L’agroforesterie peut-elle représenter un moyen de restaurer les paysages de la zone de Vavatenina ? Qu’est-ce que cela impliquerait en termes de modalités de restauration

FROM SHIFTING RICE CULTIVATION (TAVY) TO AGROFORESTRY SYSTEMS

INTRODUCTION

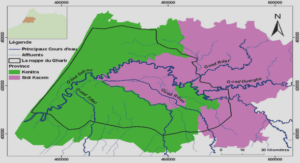

After Indonesia, Madagascar is the second biggest producer and the primary exporter of cloves and clove oil in the world, the world leader on the vanilla market and the fourth world producer of lychees (Altendorf 2018, Chalmin and Jégourel 2019). From an economic point of view, Sygygium aromaticum, Vanilla planifolia, Litchi chinensis produce the three main agricultural products exported from Madagascar (Gouzien et al. 2016). These crops are cultivated in different types of cropping systems and, in particular, in diverse agroforestry systems (AFS) managed by smallholder farmers located on the east coast of Madagascar. Today, in the Analanjirofo region (Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable.Figure 3-1), the center of clove production (Danthu et al. 2014) AFS are simultaneous associations of trees, of which the main one is the clove tree, of crops and more rarely of animals. Given the longevity of clove trees, up to 100 years (Maistre 1955), and the duration of their exploitation period, clove trees are cultivated in cropping systems that evolve with the socio-economic context and climatic events (e.g. cyclone). They are either monoculture (5-10 % in our surveys), parklands or complex multi-layered, multiJuliette Statut : Accepté Revue : Agroforestry Systems Photo : L’équipe de MadaMovie en train de mettre en place le drone pour la prise de photographies aériennes du paysage de Vohibary (2016). ©J.Mariel |From shifting rice cultivation (tavy) to agroforestry systems: a century of changing land use on the East coast of Madagascar 75 species AFS. Parklands are similar to simple AFS with annual food crops (e.g. rainfed rice, cassava, tubers, sugar cane), intercropped with clove trees growing in pastures (60-70 %). Complex AFS (20- 35 %) combine large fruit trees (lychee, mango, breadfruit, jackfruit etc.), smaller trees (coffee, citrus), herbaceous plants or lianas (vanilla, pepper) and sometimes include remaining native forest trees (Michels et al. 2010, Arimalala et al. 2019, Michel et al. 2021). The main food crop is rice, produced in paddy fields in all available lowland areas (Le Bourdiec 1974). Figure 3-1: The study area: the village of Vohibary, district of Vavatenina, Region of Analanjirofo, Madagascar Studies by Arimalala et al. (2019), Cocoual and Danthu (2018) highlight the fact that the diversity of current production systems derived from the strategies applied by the farmers in the first half of the 20th century. These strategies depended largely on the agricultural policy implemented by the French colonial power that promoted industrial crops for export, grown in large-scale colonial plantations but also cultivated by smallholders (Galliéni 1908). Arimalala et al. (2019) also showed that farmers started growing cloves, but did not apply the cultivation practices recommended by European agricultural technicians (monoculture and low planting density), thereby creating original cropping systems (AFS and high planting density) whose imprints are still visible today. These studies showed that the landscapes and farming systems on the east coast of Madagascar result from |From shifting rice cultivation (tavy) to agroforestry systems: a century of changing land use on the East coast of Madagascar 76 interactions between multiple drivers and from changes that took place over more than a century. This complex history sheds light on the agroecological contexts and farmers’ current practices. We focused on a clearly identified zone, one village and its surrounding landscape, with the aim of updating and analyzing the historical, socio-technical and economic factors that determined changes in the farmers’ strategies, production systems, and landscapes. For this purpose, we used as a baseline a monograph by an agronomist (Gérard Dandoy), published in 1973, that described the landscape of Vohibary, a small village in the Vavatenina district in 1966 (Figure 3-1). In particular, the monograph includes a land use map we compared with an updated map drawn 50 years later, based on a set of field surveys conducted in 2016. This diachronic analysis was completed by a corpus of scientific and technical references published over more than a century. First, we compared the diagnoses and maps made in 1966 and 2016 to identify the land use changes in the agricultural landscape of Vohibary. Second, we examined a set of technical and historical documents to explain these changes. Supplementary data were collected in surveys of the farmers, visits to AFS, and the testimonies of village elders.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study area The study area focused on the village of Vohibary, located 5 km from Vavatenina, the main town of Vavatenina district, and its agricultural landscape. Vohibary landscape covers an area of 210 ha whose limits are natural ridges or rivers. The natural landscape is shaped by low hills (tanety) whose altitude does not exceed 413 m with steep slopes and deep ravines excavated by tropical rainfall. Flat land is limited and lowland rice accounts for a total area of about 13 ha. Cyclones occur regularly (Donque 1975), the last major cyclones were Honorine in March 1986, Bonita in January 1996. Today, the village is composed of two hamlets, Vohibary (the original village) and Antanambo. The population mainly belongs to the Betsimisaraka ethnic group. Table 3-1 lists some characteristics of the village in 1966 reported by Dandoy (published in 1973) and updated in 2016. |From shifting rice cultivation (tavy) to agroforestry systems: a century of changing land use on the East coast of Madagascar 77 Table 3-1: Some characteristics of the village of Vohibary in 1966 (after Dandoy 1973) and in the 2016 surveys 1966 2016 One hamlet (Vohibary) Two hamlets (Vohibary and Antanambo) Population 186 inhabitants About 120 households in the two hamlets (600 inhabitants) 2.76 children/household About 3 children/household Accessibility No road, one hour on foot from Vavatenina (5 km) 2.5 km of paved road (in bad condition) then 2.5 km of track (accessible to offroad vehicles) Average size of farms 5 ha, including 1.6 ha cultivated land Between 2 and 3 ha/farm, no more available land Market / marketing methods In the village: self-consumption, local sales, barter: vegetable, edible leaves, fruits Sale of fruit, edible leaves, banana, cassava and other products at the Vavatenina market with the goods carried on the back/head; purchase of staple products (rice, salt, sugar, oil, soap, petroleum) Sale of cloves, clove oil and coffee prepared in Vavatenina (barter with Chinese traders) In the village: self-consumption, local sales, barter: rice vegetable, edible leaves, fruits Sales in Vavatenina with the goods carried on the back/head Traders come to the hamlets to collect the cloves Sale of lychees to middlemen (who work for exporters) and set up where the track meets the paved road (2.5 km from the village) Land use mapping and diachronic analysis of the study area The study area was mapped using very high spatial resolution arial photographs acquired by drone in June 2016. To ensure complete coverage of the areas overflown, the aircraft’s flight paths, and automatic release frequencies were adjusted to obtain a 60 % longitudinal overlap and a 30 % lateral overlap. The geometric distortion (fish-eye effect) caused by the type of camera on board the drone, as well as variations in the topography and in the pitch and tilt of the drone during each flight were corrected using projective transformation functions. The projections were based on several anchor points collected with a GPS or obtained from previously georeferenced and ortho-rectified satellite products. The aerial photos obtained were combined in a mosaic with a spatial resolution of 0.63 m. A total of 74 % of the study area was covered. The remaining 26 %, corresponding to valley bottoms mainly occupied by dense AFS, were mapped from satellite imagery available on the Google Earth virtual globe. Photo interpretation of the mosaic was based on in situ observations to confirm each type of land use zoning. Using the Dandoy map, particularly the main trails and paths that have barely changed since 1966, we were able to geo-reference and digitize the information, and thus to compare it with our 2016 land cover map. Most of our historical information came from old documents, journal articles and reference works written by botanists, agronomists or geographers who had resided in Madagascar since the 1900s. Most were written in French. They are listed in the bibliography. |From shifting rice cultivation (tavy) to agroforestry systems: a century of changing land use on the East coast of Madagascar 78 Surveys in Vohibary to document agroforestry practices, product uses, and local perceptions of change In 2016, the structure and composition of 12 AFSs belonging to agricultural households in Vohibary were characterized. They were selected according to the local definition of an AFS, i.e. a cultivated land with several herbaceous and perennial species in association, other than rainfed rice, and necessarily with edible species. The characterization of the studied AFS was based on farmers’ reports and in-situ observations of the number of plants of each species present in the AFS and their age class (i.e. productive or juvenile). The different types of AFS were distinguished according to these criteria, and the AFS identified helped us classify the land uses mapped by drone in 2016. We conducted surveys of the households who owned the AFS to collect data to (i) describe the different uses for selfconsumption and ways of sale of agroforestry products, (ii) estimate self-consumption of fruit and wood originating from AFS, and (iii) explore the practices used to establish an AFS. Semi-structured interviews with the village chief and the customary authorities (tangalamena) helped understand the changes that have occurred in and around Vavatenina. This information was used as inputs for our diachronic mapping analysis of the Vohibary landscape and to identify the key facts that have remained in the collective memory.

Table des matières |