Télécharger le fichier original (Mémoire de fin d’études)

State-Society Relations Theory

The role of the state or its centrality has over the years come under increased critique. As March and Olsen observe, “In contemporary theories of political science, traditional political institutions Legislature Executive Judiciary, the state, legislature and legal system; and economic institutions like the firm have receded in importance from the position they held in earlier theories of Burgess, economists like Commons and sociologists like Weber”56. Yet it has not lost its importance as a critical institution in determining political processes. Like March and Olsen state “Modern dynamics of modern institutions has necessitated examination of institutional perspective and their effect on society”. Indeed, there have been lucid analyses supporting the importance of state institutions in explaining phenomena through historical approaches57. Despite recession of significance of institutionalism, alluded to by March and Olsen, institutional perspectives have recently reappeared in explaining the importance of understanding the organization of political life58. In her work, Boone explains how land tenure institutions are critical in determination of political process in the rural economy.

The centrality of state has equally divided opinion amongst scholars of state society relations. Conceptualization of the “state” and its privileged place in government and society relations has been the subject of much scholarly attention replete with diverse approaches. The field of study encompasses divergent views relating to classical and contemporary approaches to understanding relations between government and society. A new body of literature has emerged seeking to provide new directions and perspectives that call for a rethinking of understanding of state-society relations in the context of governance. The study draws from Sellers’ perspective that provides contemporary perspectives on state-society relations (in the face of nuanced shifts from the study of government to governance) which have a useful bearing to the approach adopted in this study. Two main perspectives have been advanced59.

The first approach is a state-centred conceptualization of state society relations. Under the statist approach, the study of state society relations is about the study of the “state” itself. Seller’s states this is still the case “despite the elusiveness of stateness and fluctuating fortunes of the concept”60. The statist approach still dominates studies on state-society relations as even leading scholars in developing countries like Kohli, Migdal and Evans aiming to show the limits of the state’s authority and monopoly, still apply a Weberian conception of the state61. For instance, Migdal notes that in the contemporary world the state is perceived as the model of political order and thus it has been adopted as the means to the achievement of economic development and social modernization62. The limitations of the statist approach are evident in the assumptions that it adopts. Firstly the assumption is made that, state and society are dichotomous and mutually exclusive. Invoking the Weberian definition of the state, statist approaches assume a unitary notion of state itself63. Secondly, it is assumed that relations between the state and society can be aggregated throughout a nation State. In other words, it is problematic to conceptualize the state as a complete separate entity from society. It is also problematic to view the state as an aggregation of homogeneous state actions, institutions and policies without diversity.The state is much more than an entity comprised on homogenous state institutions and actors. It is disaggregated in different ways with diverse organizational designs, distinct unique practices and diverse functions.

Lund’s analysis on institutions and the exercise of public authority also problematizes the privileging of the state in state society relations. He proposes a refocus away from the state to also include happenings in societal activities. He posits that in order to understand how political power is exercised, we need to look into processual aspects of the formation of public authority, in particular, how it takes place in day to day social encounters64.

However, despite the criticisms on state centred approaches to state society relations, the basic concern for state-society as a field is the focus on the interactions and interdependence between state and society. There is a realization that in field of state-society relations, none of the two entities can dismiss the others importance as described by Sellers. He observes that, “Just as state-centered approaches have increasingly acknowledged the importance of society, society-centered approaches can rarely jettison state actors and institutions as an important element in explanation”65. This viewpoint is supported in Migdal’s analysis of state-society relations. Migdal theorization of state society relations notes that the relationship between the state and society is not characterized by domination of one over the other as both entities influence each other even where one is weak. The state and social organizations are continually in competition for socialcontrol. The amount of social control an organization has is ultimately determined by the number of people who follow its rules as well as by the motivations of the people in doing so. The dominant authority determines who will make rules pertaining to certain segments of the population and this may lead to a shift in the available strategies of survival for the affected individuals thus leading to conflict66. The second approach which is the society-centred approach, conceptualizes the study of State society relations as a field focused on the interactions and interdependence between state and society. The society-centred scholars have sought to reach a broad conclusion that; society provides crucial supportive elements for a state to be effective. Society-centred studies have been able to demonstrate an increasing shift away from Weberian conceptions of a unitary state and statist conceptions of state-society relations (government) towards elements of governance. A focus on governance rather than government advances the interdependence between state and society as opposed to independenceas important aspect in understanding political processes67.

Changes in focus in the study of state-society relations from government to governance is a product of the changes in society that have increasingly generated interdependence between state and society reshaping the privilege accorded to state as sole or main determinant of state-society relations68. Increased importance of the place of society in state-society relations has been reflected in emergence of new aspects of governance that demonstrate greater interdependence rather than state autonomy. Examples of the new areas of governance are manifest in; policymakers engaged in non-state organizations like nonprofits and charities in the delivery of social and a variety of public private partnerships; decentralization of important policies that have created new local channels of state-society relations; privatization of public companies and services new regulations that seek to compensate for deficiencies in unregulated markets; and, new mechanisms have provided for public and stakeholder participation in policy69.

According to Sellers, alternative empirical approaches to state-society relations have been advanced seeking to remedy the limits of understanding interaction between government and society through state-society dichotomy70. While they are still applied from the premises of “state” or “society” as main focal point, these approaches employ different empirical strategies with a focus on interactions between societal and state actors in joint processes of governance. Their attention is geared towards differentunits of analysis away from the regular concerns of typical state-centric or society centred analyses of state society relations as explained below.

Limitations of Nuanced State-society and Society centred Approaches

The state centred approach typically focuses on the “top-down” view of actors and institutions at the top of either state or societal hierarchies. The top-down view is typical to political science, public policy and public administration71. It reinforces statist approaches to state-society relations holding the traditional institutionalism presumption that state-society relations can best be understood from the perspective of public officials or other state actors majorly centering on the actions and institutions of the state.

Contemporary studies on state-society relations no longer exclusively focuses on the state and its institutions at the top but on policy making in instances of multi-level governance at thelocal or regional level, aiming to determine how public officials can act as policy entrepreneurs to bring elements of the state and society together72. As Sellers observes, “Accounts of multilevel or layered governance have gone a step further. Work in this vein demonstrates lower as well as higher levels in state hierarchies have played important roles in policy and governance, and analyzes the interplay between levels.”73

Even so, these nuanced approaches are not without a number of limitations. Firstly, the state centred approach with its tradition of generalization of characteristics of the State has been criticised for failing to capture important elements of the state. Such limitation is as a result of the conceptualization of the State as an aggregation of institutions and actors within it. Secondly, the approach privileges the role and place of state actors and institutions above other actors which has the effect of over-privileging state actors with more power to shape political processes than they actually have. Therefore, adoption of the top-down perspective as the starting point of analysis obscures the realization of equally important political processes and outcomes that occur beyond the realm of the State. In other words nuanced approach only in terms of exploring different units of analysis does not rid it off its inherent weaknesses which are attributable to its prioritization of proceeding with analysis of activities at the “top”.

On the other hand, although some society-centered approaches incorporate both “top-down” and “bottom-up”, they primarily focus on the “bottom-up” centered perspective of processes. This entails evaluation of dynamics at the local levels of state and societal organization. The society-centered approach is a popular in sociology and economics studieswhere more to attention is accorded to happenings in society than in the state74. Objectives of such disciplines, beyond the state, are focused on assessing the wider impact of the state and its policies in society. According to Sellers, society centred bottom-up approach takes a different tangent from the state centric view as it steers away from examination of interest intermediation and structuralist accounts of classes, regions or aggregated economic interests. Instead it evaluates agency in society as the main analytical focus. Its interest is in understanding consequences of governance by examining relationship between groups, individuals and their influence on processes and outcomes. It employs different strategies to demonstrate this by: separating individuals and communities from the State; stressing the role of the local or regional State;and,allowing the State to remain as a disaggregated institution capable of influences external to the State.

The main focus in society-centred accounts is given to activities occurring outside the state broadly classified into two; collective action (especially at the local level) and individual action governance. Collective action at the local level like that undertaken by community based groups is attractive to society-centred scholars as such groups possess the potential of exercising important political processes like effective local policy making, representation, civic participation and effective governance75. Individual action governance is also important as it offers opportunity for scholars to study the action of individuals, families or firms in interaction with the state. Scholars of legal mobilization examine how individuals innovatively mobilize law and legal institutions to engage with the state and hold it to account by contesting its decisions.76

The advantage of bottom-up approaches to state-society relations is that those studies are cognizant of the complexity of diverse state activities and the disaggregation of various relationships within the state. As a result, bottom-up approaches have a comprehensive appreciation of policy making processes and outcomes and the social influences on State activity. Sellers sums up the advantage of society centred accounts employing bottom-up approaches as follows, “Society-centered approaches to the analysis of state-society relations have proceeded from the disaggregated perspective of individuals and communities. This societal perspective from the bottom up offers a vantage point from which to assess the wider impact of the state and its policies in society. Simultaneously, this starting point enables an inquiry into what difference citizens, workers, neighbourhoods, or other small-scale groups and individuals have made for policy and implementation…within this general approach, distinct lines of research have adopted a range of alternative views of what it means to center analysis of the state and public policy around the vantage point of society”77.

Disadvantages of Bottom-up approaches

Bottom-up approaches to state society relations are not without their disadvantages. Important indirect state influences can be missed where Society is privileged a starting point for analysis of state-society relations78. Also, bottom up approaches focused on everyday relationships between the citizen and the state have had limited analytical value in explaining “how the shadow of the law shapes theperceptions and incentives of citizens, and have neglected to capture the ways that power relationships can shape and reshape state policy”79 To this end, bottom-up strategies should not operate as closed systems focused on societal actions only, they must consider state traditions and to what extent they affect the organization societal groups. The issue then is to examine ways of reconciling the different viewpoints adopted by top-up approaches and bottom-up approaches so that we do not miss important political processes flowing from state tradition or from the society. The question arises as to how can competing approaches be reconciled to enable comprehensive understanding of state-society relations?

Synthesis of Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches: Reconciling the Tensions

A problem of reconciliation of the respective approaches stems from fundamental traditional view-points and strategies. There are two major problems. Each approach has different ways of aggregation of different actions of different actors and institutions, that is, individuals, firms, voters and how this is generalized to wider patterns. Top-up approaches are premised on broad generalizations of local level governance units and individual actions therein80. They ignore critical aspects of individual agency and influence on local processes and outcomes. Assumptions are made about the uniformity of behaviour among individuals ignoring diversity and differentiation amongst such individuals. Such oversight of important diversity of institutions and actors is also replicated when it comes to the study of the state.

Similarly, bottom-up approaches by concentrating on the societal action may fail to capture important elements of individual action governance at top level of state institutions. Interesting aspects of contestation, deliberation and interest intermediation at the top end of both state and non-state organizational hierarchies may also not be discernible from a bottom-up perspective. Strategies focused on cases at the local level are also likely to miss developments of critical aspects of governance in other parts of the nation that would have been captured through cross-national comparative studies. Bottom up approaches fixed on employing qualitative cases have limitations in making broad generalizations about the extent to which activities they study at local level impact macro-level governance.

The second problem for both top-bottom and bottom up approaches is the reality of multi-layered governance in both state and society. This reality is reflected in Seller’s observation that “governance arrangements take place in a variety of nested settings”81. Further, because of the diversities in state (sectoral, territorial and vertical) and the variety of individuals and groups in society, it is difficult to sum up either state or society as having single common characteristics. This makes it difficult for either approach to be a perfect fit model for explaining state-society relations thus necessitating development of multi-level analyses. Multi-level analyses focused on examining multiple levels policymaking in state hierarchies. Others examine how local level policymaking feeds into national level governance. Multi-level analyses have developed as an attempt at reconciling the tensions between the four approaches to state-society relations. Scholars have sought to do this by bridging the differences through multi level analysis and incorporation of more hybrid approaches to reconcile the “top-down” and “bottom up” approaches and the “society centred” and “statist conceptions” of state-society relations.

Much as multi-level analyses have shown good promise as an integrated approach, it is yet to solve the differences in strategy advanced by each approach. Sellers states, “Multilevel analyses, and more generally hybrid approaches, hold considerable promise for advances beyond the shortcomings of each approach. Yet no single integrated approach is likely to resolve the inherent analytical tensions between macro and micro analysis as well as between the perspectives of state and society. As strategies of governance shift more toward reliance on societal actors, society-centered approaches will gain in validity. As decentralization, flexibility and local responsiveness predominate, bottom-up approaches must supplement top-down ones…The optimal mix of approaches differs with both the policysectors and the aspect of state-society relations under study. The choices also have normative implications. A society-centered, bottom-up approach, for instance, will be more likely to clarify the possibilities for movements of citizens to organize to attain power. A top down approach is more likely to be instructive about the possibilities for those who obtain power to enact effective policies”82. Therefore, the way forward is to understand the efficiency of each approach as being context specific and will much depend on the objective of the study and phenomena, the aspect of state-society relations being studied and type of institution and diversity of actors within it.

In the face of growing contemporary literature increasingly advocating for the meaning state society relations away from state, this study does not yet represent another cynic or minimalist view of the centrality of state. Rather, it seeks to represent contextualization of state-society relations in face of nuances in local political processes, with view of examining in context and specific to certain areas. Indeed following Seller’s exposition of state-society relations, even when applying a society-centered view as a starting point in evaluating collective action and individual action governance at the community level, it is acknowledged that the place of the state and its influences remains important if we want to derive a holistic understanding of state-society relations under study. The problem here is not in the sense of the presence of the state in understanding state-society relations but in the traditional conceptualization of “state” as unitary state. The problem is that in the Weberian sense, the state is paramount in relation to the state, has monopoly over exercise of public authority. That governance comes from a single source, that is, the “state”. That in state-society interaction, there is one way of understanding as a vertical dominance of state over its interaction with society. That governance is one-dimensional as it flows from the state towards controlling society and cannot be vice versa.

Despite inclination to society-centred perspectives, the study does encompass an examination of the nature of the state more so its place in state-society relations. The study seeks to examine state-society relations as a dimension of changing non state policing practices in local units in Kisii County. In explaining this, the study seeks to advance a moving away from understanding or viewing of state-society relations from state-centric viewpoint and the view that state-society relations are solely shaped by the state.

Synergy Strategies in State-Society Relations

Because new forms of local policing in Kisii County engage state and societal actors, the objectives of investigation are focused on how the state and society based actors relate when they interact as co-participants in local governance arrangements with objective of maintenance of law and order. Beyond this it is also important to evaluate the synergies created by co-existence of government and society in such governance arrangements. It is not assumed that the combined action between state and societal institutions is automatically complementary; rather, it encompasses examination of both instances of collaboration and competition.

Scholars have explored the question of state-society synergies through different dimensions looking at the importance of andeffective strategies for such synergies. According to Brenya and Warden, scholars like Evans have advocated for a synergy between state and society as an essential approach to addressing the issue of developmental challenges owing to a perceived failure of the state in driving developmental agenda83.

Evans views achievement of state-society synergy as involving three strategies, namely; endowments’, constructability, and, the social capital perspectives84. Under the endowments’ view the success of state-society synergy is contingent upon pre-existing features of the society and the polity. The constructability perspective is concerned with building synergy for the short term rather than for posterity. The social capital perspective is the one that creates an effective synergetic partnership85.

For Evans, social capital perceives state-society synergy beyond the theory of development to incorporate the “importance of informal norms as valuable economic assets that makespeople collectively productive”86.According to Brenya and Warden, analysis by Evans refers to a specific kind of synergy for a link to be created between informal ties and development87. Such synergy is defined by civic engagement which strengthens state institutions and the state institutions reciprocate by creating conducive environments for civic engagement. For Evans, a governance arrangement that involves the informal (society in particular involving civic actors) and invokes an interaction based on reciprocity is likely to strengthen the state itself and result in an effective synergy.

Evans also differentiates between complementarity and embeddedness in situating effective strategy for state-society relations where complementarity refers to mutually supporting relations between public and private actors. Complementarity is suggestive of a dichotomy between state and societal institutions. The actors conceptualized as “public” and “private” are taken to be separate distinct entities that are still expected to deliver better developmental outcomes.

Further, Evans uses the term embeddedness to refer to the creation of synergy based on everyday public-private interactions and the norms and ties that build up as a result of such interactions88. This resonates well with social capital strategy which puts the place of everyday interactive civic-government ties at the centre of effective synergies.

The discussion above may be viewed as discussion of state-society relations through state-conception of state-society and society-centred conceptions of politics (state-society relations), where the study seeks to adopt the latter with a qualification as to the importance of state. In relation to the place of law, the study similarly urges a refocus away from the conceptualization of law of “what law is” as formal law, which conception, it is submitted here, amounts to what the study refers to as a state-centered conception of law. That law must be understood exclusively as positive law, of pure value, only capable of being sourced in formal text, and authorised or developed by the State. It must be of purecontent and value without any other influence whatsoever be it morality or other foundation outside the law itself. Law is also understood as rule of law. While the place of formal law has its application, it is equally important to examine the law in action where it has been enacted to apply to society. It is vital to observe everyday applications of law in the context of daily social, cultural, legal and political practices as it occurs in society. Hence alternative perspectives of laware applicable and in that regards the legal sociology perspectivepossesses comparative competence over other theories in providing a comprehensive understanding to society-centred understanding of law.

Table des matières

CHAPTER ONE GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1.1Background to the Problem

1.2 Statement of the Problem

1.3 Theoretical Framework

1.4 Objectives of the study

1.5 Research Questions

1.6 Hypothesis

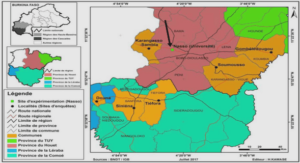

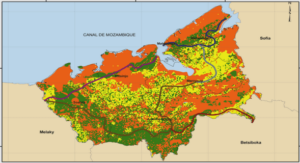

1.7 Site of Study

1.7.1 Kenya

1.7.2 Kisii

1.8. Research Methodology

1.9 Chapter Breakdown

CHAPTER TWO STATE SOCIETY RELATIONS AND LEGAL SOCIOLOGY IN GOVERNANCE

Introduction

2.1 State Society Relations Theory

2.1.2 Synthesis of Top-down and Bottom up Approaches

2.1.3Synergy Strategies in State-Society Relations

2.2Rational-Legal Authority

2.2.1 Rule of Law Approaches

2.2.2Rational Domination

2.2.3 Rational Legal Authority and Law and Order

2.3. Theories on Relationship between Law and Society

2.3.1 Law and Society as Function and Consensus

2.3.2 Law and Society as Conflict

2.3.3 Sociological Jurisprudence

2.4 State Society Relations and Legal Sociology in Governance

Conclusion

CHAPTER THREE HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL FOUNDATIONS OF STATE POLICING

Introduction

3.1 Policing and Administration of Justice in Pre-colonial Gusii

3.1.1Political Organization

3.1.2 Administration of Justice

3.1.3 Law Enforcement in Colonial Kisii: Competing Institutions

3.2 Context of Policing in Regimes since Independence

3.3 History and Politics of State Policing

3.3.1 Colonial Policing: 1887-1963

3.3.2 Kenyatta: 1963-1978

3.3.3Moi Government: 1978-2002

3.3.4Kibaki Government: 2003-2010

3.4History of Continuities

Conclusion

CHAPTER FOUR POLICING REFORM AND REGULATION: CONSTITUTIONAL AND LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK – 2010-2016

Introduction

4.1 Post-constitutional Reform: 2010-2013

4.1.1Strengthened Constitutional Framework

4.1.2 Institutionalization of Joint Command

4.1.3 Accountability

4.1.4 Operational Efficiency

4.1.5 Decentralization of Police Services

4.1.6 Challenges

4.2. Prevention of Organized Crime Act

4.2.1 Objective and Rationale of the Act

4.2.2 Definition(s) of Organized Crime

4.2.3 Membership

4.2.4 Retention of Material Benefits

4.2.5 Use of threat of violence

4.2.6 Possession offences

4.2.7 Obstruction of Justice

4.2.8 Remedies

4.2.9Declaration Provisions

4.3 Cases on Sungusungu in Kisii

4.4. Evaluation of POCA

Conclusion

PART II

CHAPTER FIVE OCAL POLICING IN KISII COUNTY: HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF SUNGUSUNGU 1990-2016

Introduction

5.1 History of Sungusungu inTanzania: From Ruga-Ruga to Sungusungu

5.1.1 Ruga-Ruga: 1880-1918

5.1.2 Return of Ruga: 1914-1918

5.1.3 Political and Socioeconomic Context in Tanzania

5.1.4Emergence of Sungusungu in Tanzania

5.1.5Reasons for Emergence of Sungusungu in Tanzania

5.1.6Sungusungu in Kuria land

5.1.7Spread of Sungusungu to Kisii

5.2 Contemporary Sungusungu in Kisii

5.3 Organizational Structure

5.3.1 Leadership

5.4Mode of Operation

5.5Financing

5.6 Role in Elections

5.7 Challenges in Everyday Policing

Conclusion

CHAPTER SIX NUANCES IN LOCAL POLICING: EMERGENCE OFOFFICIAL COMMUNITY POLICING IN KISII COUNTY: 2010-2016

Introduction

6.1 Community Policing in Kenya

6.2 Community Policing in Kisii

6.2.1Sungusungu in Taracha Location

6.2.2 Community Policing in Taracha Location

6.3. Origin of Official Community Policing

6.3.1 Establishment

6.3.2 Organizational Structure

6.3.3Mode of Operation

6.3.4 Financing

6.4. Challenges in Everyday Policing

CHAPTER 7 VIGILANTISM TO COMMUNITY POLICING: DYNAMICS CONTINUTIES AND TRANSITIONS

Introduction

7.1 Similarities and Differences

7.1.1Establishment and Organizational Structure

7.1.2 Mode and Sphere of Operation

7.1.3Financing

7.1.4 Elections and Political Patronage

7.1.5 Use of Violence

7.1.6 Socio-cultural Dynamics

7.2Interplay between Law and Sungusungu

7.2.1 Change of Identity

7.2.2 Disintegration of Sungusungu

7.3Law and Community Policing

7.3.1 Adherence to the Law

7.4 State and Sungusungu

7.4. 1 Privatisation of Security

7.4.2 Direct Participation

7.5. State and Community Policing

7.5.1Official Community Policing and State Relations

7.6. Official Community Policing: Continuities from Sungusungu

7.6.1 Relationship between Community Policing and Citizens

7.6.2 Realities on Inclusive Governance: Women Participation

7.6.3 (Under) Representation of Youth in Leadership

7.6.4 Lack of opportunities for Youth

Conclusion

CHAPTER 8 CONCLUSIONS IMPLICATIONS AND PROSPECTS

Introduction

8.1 Conclusions

8.1.1Place of Law in Nature of Policing

8.1.2 Political Processes

8.2. Implications

8.2.1 Place of Law

8.2.2State-society

8.2.3Local Policing: Vigilantism and Community Policing

8.2.4Traditional Governance and Culture

8.2.5Youth

8.3. Prospects

8.3.1Police Reform

8.3.2 Harmonization of Legal and Policy Reform

BIBLIOGRAPHY

APPENDICES