Defining Territorial Governance

What is a Territory?

To be able to describe the territorial governance of energy and its relationship with the modern Citizen Energy movement in France, we must first arrive at a definition of territory that suits our purposes and have some idea of how a given territory comes into being. To attempt to clarify what is often considered an excessively vague concept (Torre, 2015) we will first examine the different facets of the concept before bringing them together. A territory, as a geographic entity, is a physical space on the earth with borders and a total extent influenced by, among other things, topography of physical features such as rivers or mountains. As we will see in our discussion of geographic proximities, this is a crucial dimension, as many territories are delineated based on measures of time and distance for travel from one place to another. Similarly, the historical political forces which set those borders have been influenced by geography. This relationship leads to the next conception of territory. The administrative aspect of a territory generally springs naturally to mind as well. Here, the territory is understood as the area of operation of a government actor that does not overlap with other government actors of the same scale and is formally independent from them. A department exists within a region, within France, and within Europe, but no department can overlap with another one, for example. This very naturally poses the question of multi-scalar understandings of territory, which can complicate discussions on this topic. If a given point on a map can be within multiple territories at once, and administrated by many levels of government at the same time, the articulations between each territory and both the higher-order ones containing it and the lower-order ones contained by it (as well as those outside of it or overlapping it) become an important part of the definitions of each of those entities. An administrative understanding of territory is closely related to its historical dimension.

From a historical perspective, a territory is the sum of the major events and figures involved in giving it the shape and character it has today. Many territories were born and disappeared in the geographic zone that we now refer to as France, and each of them has left their mark on the culture, customs, languages, and borders of the modern nation-state. The territory’s history continues to shape it concretely, in the forms of infrastructure, political institutions, and its productive systems. France, viewed in this way, is the sum of all of this history that led to the country we see today. In particular, the historical elements that make up the popular imaginations of the inhabitants of the territory, and those who consider it from the exterior, build the “story” of the territory that people tell themselves and others about it.

This narrative character embedded in society is the last approach that we will highlight here, although there are many others that we could. Put simply, in a social dimension, a territory is any place where the people who believe that they live in that territory, and attach some importance to it, live. Geographically, this can correspond to a lost historical territory, like the old region of Bourgogne, or to a bioregion, or some other shared construction of identity for its inhabitants. Its nature, along with what it means to live there or be from there, is are shared and evolving social constructions. The definition of territory that we are using for this study embraces all of these elements. Torre (2019), in an article on proximity relations and their role in both territorial development and governance, provides hints as to what a territory is, by first saying what it is not: “Territories are not mere geographical entities, but also collective productions resulting from the actions of a human group, with its citizens, its governance mechanisms and its organization. They are in continuous, long-term construction and develops through oppositions and compromises between local and external actors. They are characterized by a history and preoccupations rooted in local cultures and habits, a perceived sense of belonging, as well as modes of political authorities and specific organization and functioning rules.” This description brings together all of the dimensions discussed in this section, underlining the fact that a territory is the constantly changing sum of many parts. Going further, Leloup (2011) suggests describing territories and their development using the framework of complex socioeconomic systems, irreducible to the sum of their parts. While agreeing with the systemic character of the territory, Lamara (2009) underlines the importance of previously unidentified or unexploited territorial resources in the construction of a territory. Helpfully, these wide definitions focusing on the dynamic and systemic aspects of territory allow us to take a vast array of factors into account when studying the actors and relationships at play. Less helpfully, they greatly increase the difficulty of describing the totality of the forces operating there. While maintaining our attachment to this rich understanding of territory, we choose to focus most of our attention in this study on the actors, their relationships, and the different ways in which they are in proximity with one another. It is this approach through socio-economic proximities that will be our starting point in pursuing a more thorough understanding of territorial dynamics and what contributes to making each territory unique.

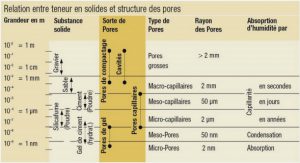

Constructing Territory out of Proximities

Prominent scholars on the questions of territorial governance and development hold that the many of the basic building blocks and driving forces underlying a territory, its construction, and its evolution can be understood in terms of proximities, both geographic and organized (Leloup et al, 2005; Torre, 2019). Their work has served to bring depth and texture to the analysis of territory, which has too long been treated as a neutral point in space by economics. The proximities approach to the socio economic analysis of territories is a relatively recent development, with the first systematic proposals for methodology dating back to the early 1990s (Bouba-Olga & Grossetti, 2008). Given both its newness and its growth in popularity over the past 10 years (Torre, 2019), it is unsurprising that a variety of definitions and schemas exist for describing and classifying proximity. For this study, we have chosen to adopt the simple two-proximity framework of Torre and Rallet (2005), which easily maps onto the Pecqueur and Zimmerman (2004) three-proximity framework. In both cases, the analysis of proximity relationships and their role in defining a territory begin with geographic proximity. Geographic proximity is a relationship between two or more objects of study, usually socio-economic actors (i.e. organizations or individuals), specifically: “Geographical proximity is above all about distance. In its simplest definition, it is the number of meters or kilometres [sic] that separate two entities. But it is relative in three ways: in terms of the morphological characteristics of the spaces in which activities take place. In terms of the availability of transport infrastructure. In terms of the financial resources of the individuals who use these transport infrastructures. (Torre, 2019)” The inclusion of time and cost, and not only physical distance, makes it clear that proximity is mediated by infrastructure and socio economic structures of inequality, as well as raw geography. Two people connected by a low-cost high-speed rail line are “closer” to one another than two people separated by a mountain range, even if the number of kilometers separating each pair is the same. Similarly, a pair of wealthy people living on opposite ends of that same high-speed rail line should be thought of as being in greater spatial proximity to one another than a pair of poor people. Geographic proximity, then, should be understood not only as the physical distance between two objects, but also as the time and resource costs required to reduce that distance to zero, relative to the available resources of the actors in question. This form of proximity is the first and most important one in the definition of a territory. Most obviously, geographic proximity circumscribes the area that a territory covers. Describing the process by which a territory comes into being, Leloup et al. place this proximity center stage: “It is built thanks to longstanding relations of geographic proximity between a wide variety of actors; these “neighbor” relations can lead to concrete actions and even the creation of common norms” (Leloup et al., 2005) Spatial proximity is thus the basic precondition for the construction of a territory; the ability for actors to interact cheaply and easily, both when they choose to and by happenstance, allows relationships to form between them. The relationships open the door to the creation of organized proximities. Drawing on their previous work in the field, Torre (2019) explains that organized proximity refers to: “the different ways of being close to other actors, regardless of the degree of geographical proximity between individuals.” This somewhat vast description is then specified by breaking it into two sub-categories: a logic of belonging and a logic of similarity. Organized proximity based on a logic of belonging (organized-belonging) refers to the degree to which two actors are close to one another within a network of relationships. This specific form of proximity can be understood as roughly equivalent to organizational proximity from the work of Pecueur & Zimmerman (2004). Borrowing from the literature on social embeddedness, such as the works of Granovetter (1973, 2005), organized-belonging proximity can be understood as the distance between two or more actors on a graph of a social network in which those actors are represented by points and the ties between them as lines of various weights. The weights of these ties represent their strength, with stronger ties being those that we invest more time and resources into and tend to have greater trust in. The fewer ties that are needed to bridge the shortest distance between two actors, the more those actors are in proximity to one another. This form of proximity is one of the primary determinants of the spread of information through a social network, with different network structures having different impacts on the speed and quality of information spread. Broadly, the closer two actors are to one another in the relationship graph the more easily information will pass from one to the other. By extension, if actors are arranged in a dense relationship graph (i.e. one in which each actor has multiple short relational pathways to reach each other actor), they are more likely to share the same set of information. Dense networks tend to be associated with strong shared social norms as they are easier to enforce and more regularly reinforced from multiple other actors in the network (Granovetter, 2005). This dynamic is the inverse of Granovetter’s (1973) famous demonstration of the strength of weak ties, in which he shows that weak ties are more likely to provide novel information than strong ones, specifically because they tend to bridge gaps between otherwise disconnected social networks. We can easily see how the nature of the networks present in a given geographic area would be important determinants for the nature of territory in that place. Extending Granovetter’s arguments, we can posit that differences in network arrangements in a geographic area are reflected in differences in the territorial system there. An area characterized by many small, tight-knit social groups with strong ties internally that are only distantly connected to one another will not tend to circulate information rapidly through the network, but will tend to have robust, locally shared social norms and ideas about the world.

The “echo chamber” effect tends to reinforce shared norms and motivate action through imitation of others in the network (Granovetter, 2005). This might correspond to a rural zone in which the local topography and infrastructure makes travel between villages difficult, and in which most economic and social activity occurs at the level of family units. On the other hand, an area in which many people have many weak ties to many others, information will tend to move quickly through the network but the ability to enforce social norms or construct a shared representation of the territory (and who belongs) will be reduced. This is typical in a metropolitan setting with many different groups freely mixing with each other.

However, it is important to avoid caricaturing all rural zones as isolated and clannish and all urban areas as places of constant interaction and openness. A set of villages in the countryside that come together for regular markets, all contain workers in a nearby factory, and that maintain a vibrant scene for cultural events will be characterized by a “looser” network arrangement. Similarly, an urban area in which multiple tight-knit communities (ethnic, religious, class-based, or otherwise) exist side by side with little interaction might have dense, isolated networks. These different arrangements of the structures of organized-belonging proximity are both influenced by and influence the third form of proximity we will discuss here: organized-similarity.

Organized proximity based on a logic of similarity “corresponds to a mental adherence to common categories; it manifests itself in small cognitive distances between some individuals. They can be people who are connected to one another through common projects, or share the same cultural, religious (etc.) values or symbols.” (Torre, 2019) This form of proximity can be read as equivalent to Pecueur & Zimmerman’s (2004) institutional proximity, in that these projects, values, and symbols are all themselves institutions in the socio-economic sense. Torre goes on to say that this form of proximity can either develop within reciprocal relationships between actors, such as within a social network, or emerge from some pre-existing commonality between strangers and thus facilitate communication, such as being a part of a common diaspora. This form of proximity is then both a result and a facilitator of organizedbelonging proximity. It is important to note that the shared ideas of any given organizedsimilarity proximity must, implicitly, contain some rules for inclusion and exclusion (Torre, 2019). For example, to be a “true” member of a diaspora, you may be expected to adhere to some set of religious, political, or moral beliefs or perhaps practice some set of expected behaviors. These rules can be contested and can evolve, but the fact remains that the construction of a common category that allows for organized-belonging proximity also means the exclusion of some actors. The marking of borders, both geographic and conceptual, takes center stage when we consider the form of organized-similarity that is most relevant to this study: the shared idea of a territory.

This dynamic is made explicit by Leloup et al. “a territory defines itself with respect to its environment. It results from a process of discrimination, from a dynamic of construction of an “inside” as opposed to an “outside.” (2005) Construction of these borders happens along multiple lines, geographic of course but also frequently in terms of history, culture, ethnicity, or religion. The idea of the territory is itself a common category, or institution, which brings those that are seen as being “within” into organized-similarity proximity with one another and pushes those defined as “without” further away. Importantly, since the definitions of the different borders of the territory are not necessarily identical between actors, the similarity of their definitions of what it means to belong also constitutes a sort of organized proximity. Two people may agree that they both belong to the same territory, but if they hold irreconcilable views of what that means (for example a conception natural spaces to be preserved and admired versus a wild land to be civilized and exploited) they are not especially close to one another in this respect. Here again, various territories will have very different arrangements of this form of proximity: some will have a very consistent shared view of the various kinds of borders that define their “within” and their “without” and this group definition will both result in and result from tighter social relations, while others will house many different ideas of what it means to belong and the social norms that go along with it. As we have seen, the three proximities that we have discussed here combine with other local factors (climactic, geological, agricultural, etc.) to define the borders and nature of the territory in question.

Introduction |